Need to promote students’ academic and social development? Storytelling is an efficient and powerful language activity that impacts reading, writing and social skills. It easily integrates into classroom routines too!

By Trina Spencer and Chelsea Pierce

Download PDF

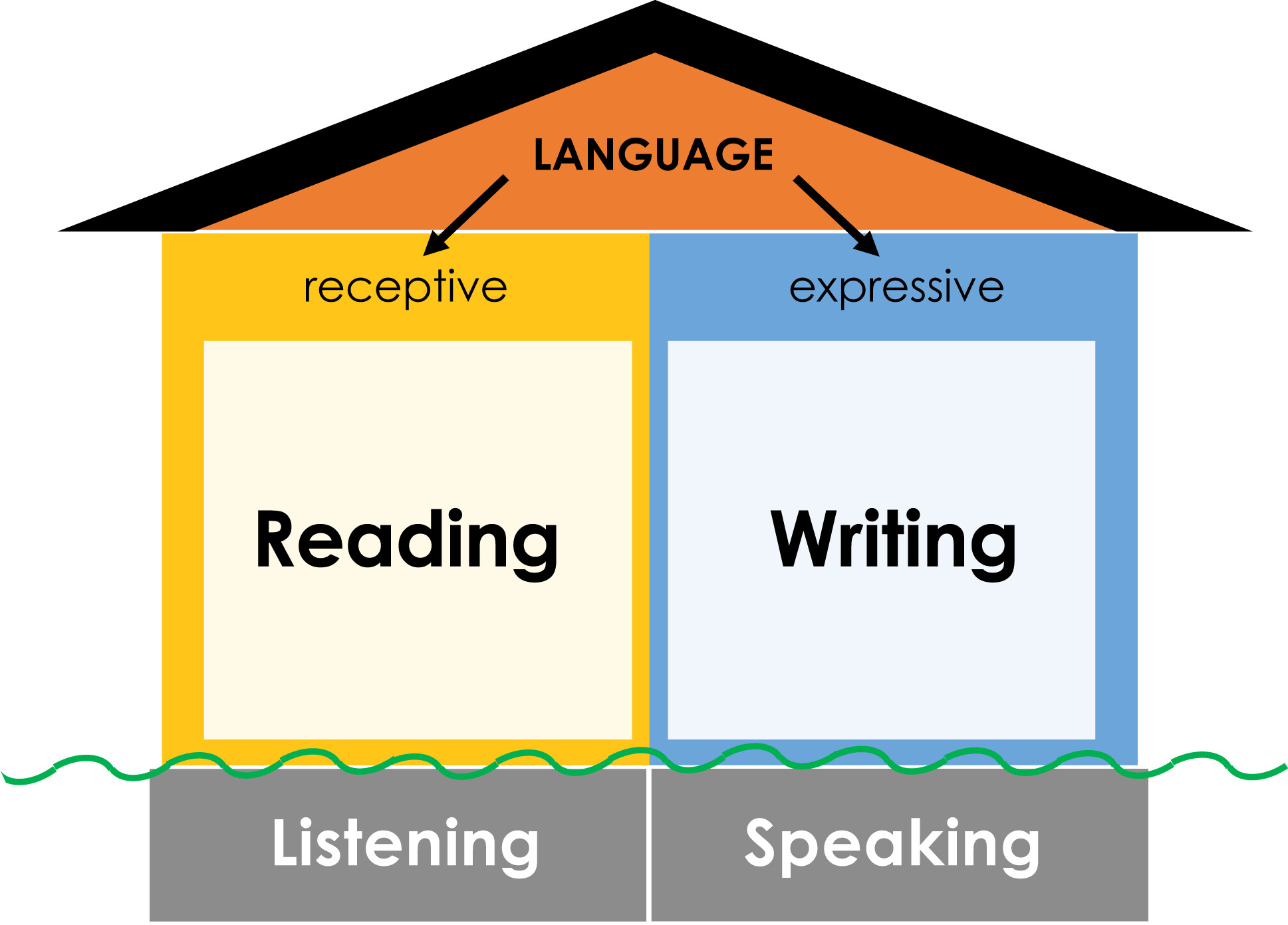

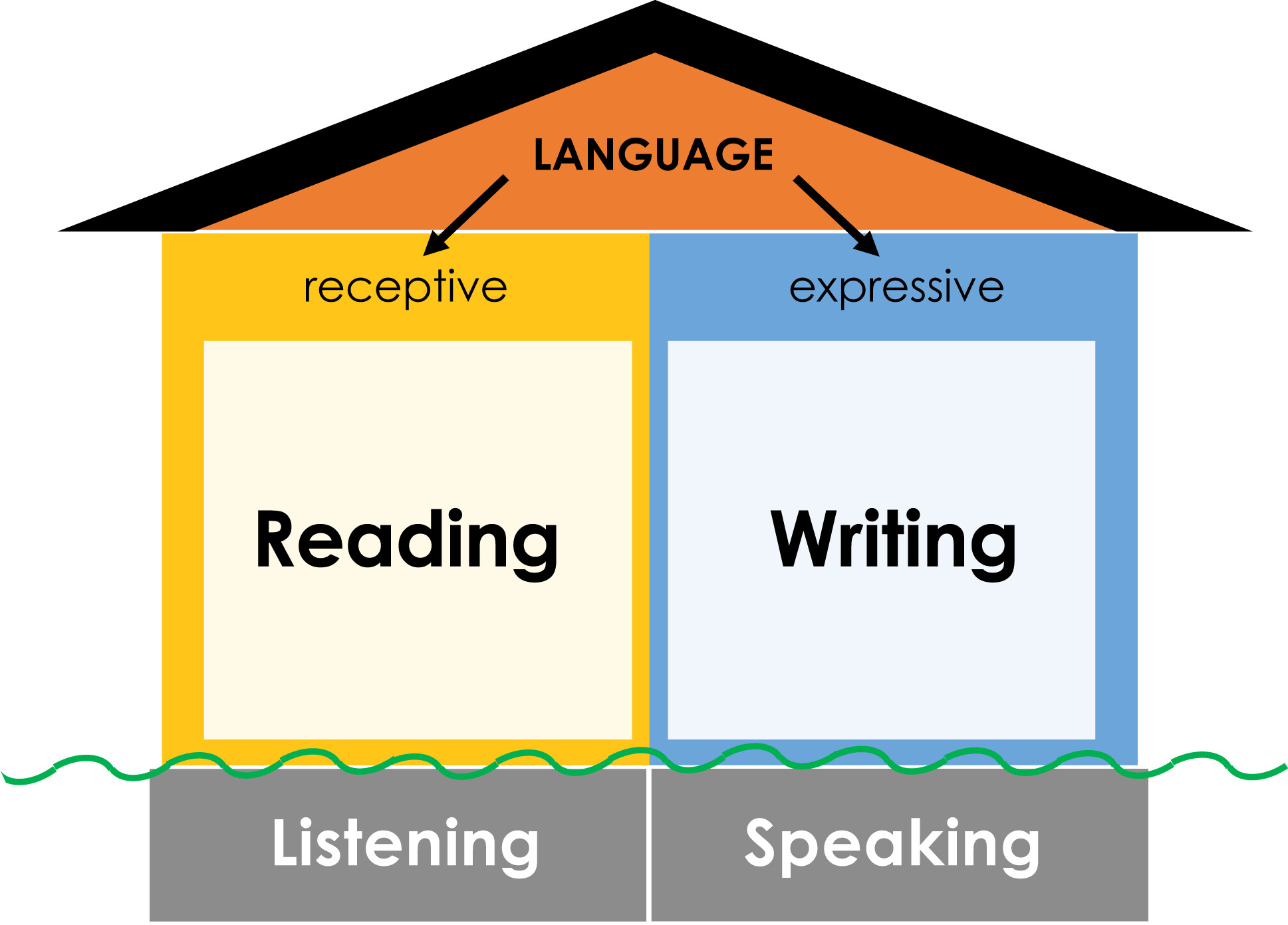

The notion that speaking and listening skills are a necessary foundation for reading and writing is well established and pervasive in the United States’ academic standards (see Figure 1; National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010). Students’ listening comprehension significantly predicts their reading comprehension (Babayiğit et al., 2020) and expressive language (i.e., speaking) fosters writing performance (Bishop & Clarkson, 2003). Extensive research documents the central role of oral language skills such as vocabulary, discourse structures and grammatical knowledge for literacy development (Kim et al., 2015; Lervåg et al., 2017).

Figure 1

U.S. students represent a diverse group with distinct differences in preparation for the oral language demands of academic environments. For example, many students with disabilities experience difficulty learning oral language naturally (Norbury et al., 2016), which negatively impacts their attainment of reading and writing skills (Bishop & Clarkson, 2003; Mackie et al., 2013). Students who speak a non-English language or a non-mainstream dialect of English at home may enter U.S. schools with less experience in the language (and type of language) in which reading and writing instruction takes place. The effects of poverty can also exacerbate students’ oral language differences (DeNavas-Walt et al., 2013). Without the foundational oral language skills firmly established, students struggle to acquire successful reading and writing repertoires (National Center for Education Statistics, 2011, 2019).

In addition to its pivotal role in the development of reading and writing, oral language is necessary for social interactions and social–emotional well-being. Early oral language skills are one of the best predictors of later social skills (Pace et al., 2019) and difficulties expressing one’s self is linked to behaviour problems (Chow et al., 2018). Without regular exposure to sophisticated school language due to the COVID pandemic, students’ oral language acumen, especially as it relates to social–emotional development, is suffering. Oral communication and social exchanges are further inhibited by wearing masks. As a result, schools (over 90% of respondents) are concerned about the impact of reduced oral language exposure on students’ language and social development (Bowyer-Crane et al., 2021).

Given the large percentage of students who would benefit from intentional oral language instruction (Kieffer & Vukovic, 2012; Nakamoto et al., 2007) and the enormity of the current pandemic context, it can be overwhelming for teachers to address the diversity of students’ needs in their classrooms. Avoiding the suggestion that teachers need to become language experts, science of reading experts recommend teachers focus on a few critical oral language repertoires, which include vocabulary, grammar and syntax, and text structures (Cervetti et al., 2020; Phillips Galloway et al., 2020). This cluster of language features is often referred to as academic language. As opposed to conversational language, academic language is primarily used in school to acquire and express knowledge (Snow & Uccelli, 2009) and involves “word-, sentence-, and discourse-level language patterns” (Phillips Galloway et al., 2020, p. 331). Although there are some differences between oral and written academic language, there are also shared features. As a result, oral academic language has been identified as a pivotal skill repertoire (Snow & Uccelli, 2009) for boosting reading and writing achievement among all students. Knowledge of vocabulary, sentence structures and discourse patterns aid social communication too.

The case for narratives

Schema theory (Mandler, 1984) posits a cognitive bridge between oral and written language that results from shared features. Whether spoken or written, narratives share word-, sentence-, and discourse-level patterns (Pinto et al., 2015), and therefore form a suitable bridge for transferring oral academic language to written modalities (Spencer & Petersen, 2018b; Westby et al., 1994). This theoretical framework is bolstered by numerous correlational and causal investigations. For example, early narrative language predicts academic achievement (Bishop & Edmondson, 1987), especially reading comprehension in the fourth, seventh and tenth grades (Snow et al., 2007), and writing (Kim et al., 2015). There is also convincing evidence that narrative- focused oral interventions improve students’ reading comprehension (Clarke et al., 2010; Petersen et al., 2020) and writing skills (Petersen et al., 2022; Spencer & Petersen, 2018b).

Narrative has many definitions, depending on which discipline and literature are consulted. Sometimes, narrative is referred to as a genre in parallel to exposition (Gottlieb & Ernst- Slavit, 2014); sometimes, narrative is a device for making sense of emotionally charged experiences and trauma (Richardson, 2000) or a basic principle of mind that organises our thinking (Turner, 1996). For classroom purposes, we choose to define a narrative as the monologic telling or retelling of a real or imaginary past event, with causally related elements presented in temporal order, in spoken or written form. Simply put, narratives are stories.

Storytelling is a common communication modality that emerges as young as two years old in typically developing children (McCabe, 2017). The plot of the story requires proper sequencing of macrostructural episodic components – problem, action, consequence – to give an organisational backbone to it. Additional components include character, setting, feeling, complication and resolution or ending. These elements are arranged according to rules about their order and grouping called story grammar (Stein & Glenn, 1979). Story grammar provides the latticework of generative language much like a trellis offers a stable structure around which ivy grows. The story grammar framework of narratives has been adopted by U.S. schools and is pervasive in the Common Core State Standards (National Governors Association, Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010). Explicit or tacit understanding of narratives at the discourse level is necessary to understand literature at all levels of complexity.

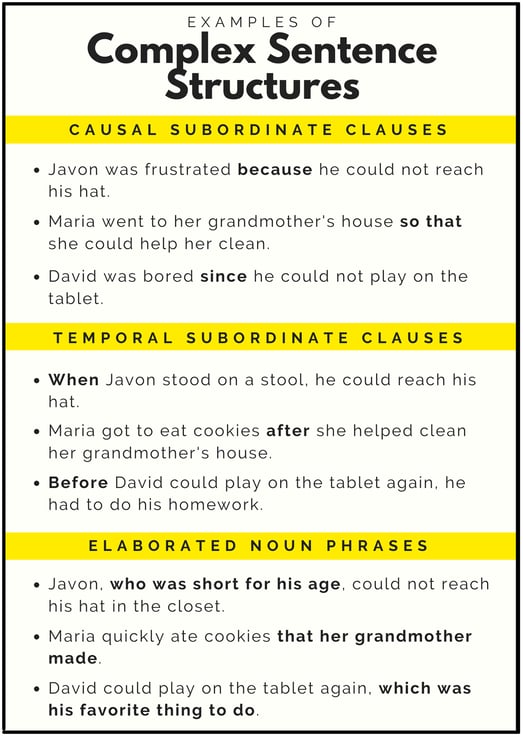

Narrative elements within the story grammar framework form a useful schema (Mandler, 1984) that helps to order causally and temporally related events, but comprehension also requires knowledge of words and sentence structures. Because listeners and readers are naïve to a storyteller’s experiences, narratives necessitate the use of sophisticated, descriptive language (i.e., narrative language). For example, storytellers make use of causal and temporal subordinate clauses, as well as elaborated noun phrases, adjectives and adverbs to paint clear pictures for their listeners or readers (Benson, 2009). In addition to the word-, sentence- and discourse-level patterns available, narratives naturally integrate several cognitive abilities such as attention, memory, inferencing and theory of mind (Curenton, 2011). As students learn to understand and produce narratives, they simultaneously learn to orchestrate the converging cognitive and linguistic processes needed for skilled reading and writing.

While the link to reading comprehension and writing is convincing by itself, there are additional reasons to use narratives in the classroom. Storytelling is fun, ubiquitous, culturally flexible and socially important. The natural consequence of telling a story is attention, which is the most common form of approval. Children want to tell stories and gain approval from adults (e.g., “How was your day?”) and peers (e.g., “That happened to me once.”). Parents of children with disabilities wish for their children to be able to report about school events (Pituch et al., 2011) and children who are good storytellers are more popular among peers (McCabe & Marshall, 2006). Students do not need to be cajoled during storytelling exchanges because they generally enjoy talking about preferred topics or themselves. Furthermore, stories about personal experiences are the most common type of narrative children produce (Preece, 1987), making the teaching of narrative skills immediately useful for social contexts. Narrative communication could be leveraged to express trauma or report abuses, thereby providing a layer of protection for children (Fong et al., 2020). Although there can be cultural differences in storytelling styles and structures, narratives are common in most cultures (Westby, 1994) and can be tailored for cultural, personal and situational relevance (Curenton, 2006, 2011).

In typical development, narratives and the academic language features are established in students’ oral language repertoires before they are expected in informational discourse and written form (Curenton, 2011). Oral language skills acquired through parents’ bedtime stories and book reading are later integrated with students’ code skills (i.e., decoding and spelling) to convert oral language experiences into written language success. However, students without oral narrative proficiency may struggle to make that conversion when written text is present. Similarly, students without fluent word reading skills may miss opportunities to advance their academic language. A series of studies led researchers to conclude that “comprehension-building interventions may be most beneficial when presented in a format that does not require extensive other skills such as decoding” (van den Broek et al., 2011, p. 265).

There is also the issue of cognitive load. When students are asked to work on word reading and comprehension at the same time and their decoding is not automatic, all their cognitive energy is spent on decoding with little left for comprehending. If comprehension is worked on without text, then their attention is reserved for learning vocabulary, sentence structures, and discourse structures that will transfer to written language when their code skills are proficient (van den Broek et al., 2011). Finally, students are less likely to resist oral language tasks, especially oral storytelling activities, because they are generally easier, more fun and perceived as more relevant and useful (Curenton, 2006).

Recommendations for infusing oral storytelling in classrooms

In the remainder of this article, we present seven recommendations for infusing oral storytelling in classrooms. Because we focus on the practical and implementable aspects of oral storytelling, there is insufficient space to cover the theoretical and empirical grounding for each of the recommendations. Nonetheless, schema theory (Mandler, 1984), theories of learning (Engleman & Carnine, 1991), and an extensive research base related to effective instructional design (e.g., Watkins & Slocum, 2004) and narrative-based interventions (Favot et al., 2020; Pico et al., 2021; Stetter & Hughes, 2010) informed their selection for inclusion here. The specific recommendations were chosen because they can be put into practice tomorrow without extensive preparation or the purchase of materials.

Teach using retelling, then generalise to personal and fictional generations

Retelling is considered one of the most valid methods of measuring comprehension, whether one hears or reads a passage (Reed & Vaughn, 2012).

It is a critical skill that integrates both listening for understanding and then expressing one’s understanding. Working on retelling, at a minimum, sharpens students’ ability to listen for patterns in stories and then organise their understanding using the relations between story events.

As retelling is a critical comprehension skill, necessary for both oral and written language comprehension, it is a great place to begin. However, in the context of oral storytelling, retelling is considered a stepping stone to more complex expressions of oral language such as personal and fictional stories. It is easier to begin teaching narratives (i.e., discourse structure) and narrative language (i.e., vocab and complex sentences) within the context of story retell activities before transferring students’ knowledge of narrative to the creation of their own stories. After retelling a modelled story, teachers can ask students, “Has something like that ever happened to you?” and provide support as students generate personal stories (Spencer & Slocum, 2010). Because personal stories are the form of communication students are most likely to use with friends and family, students who learn the linguistics of personal stories (e.g., past tense, first person) can put it into practice immediately. Personal stories are also needed to express emotions and report adverse experiences. Once students regularly tell personal stories, they are ready to create fictional stories, which are in higher demand at school. If students can develop personal and fictional generation skills via oral language, they will be better prepared to engage in personal and fictional writing tasks.

Model simple stories and increase their complexity over time

To not overwhelm or frustrate students with nascent oral language repertoires, begin with short, simple stories. Because retelling is an expressive language task dependent on a listening task, it involves the integration of cognitive-linguistic repertoires. It is truly a complex academic skill to retell something.

Students benefit from the language they hear when someone reads to them; however, children’s literature is not developmentally appropriate for students’ expressive language (Curenton & Craig, 2011).

For story retelling activities, teachers should choose stories that are more difficult than what the students can decode but not as complex as what adults would read to them. Selecting the right type of story can be nuanced, which is why some published storytelling interventions include short and simple stories for retell practice (e.g., SKILL, Gillam & Gillam, 2016; Story Champs, Spencer & Petersen, 2018a). It is not imperative to use commercialised narrative programs. What is important is that students begin with a length and complexity of story within their zone of proximal development. In other words, select, create or adapt stories that students may struggle to retell themselves, but can retell with teacher support. As students gain confidence and proficiency, increase the length and complexity of the stories in terms of narrative structure, complexity of sentences and novelty of vocabulary.

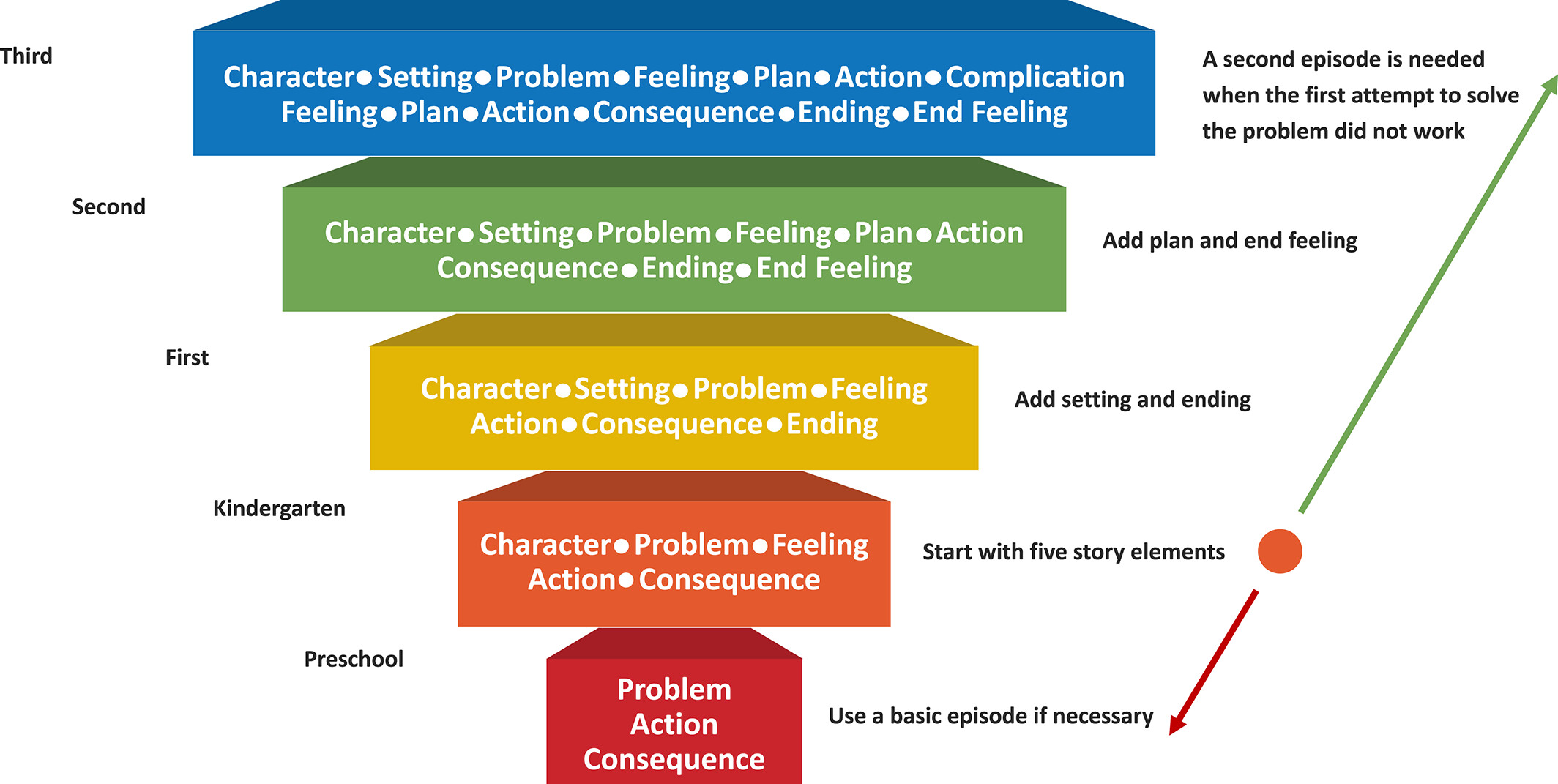

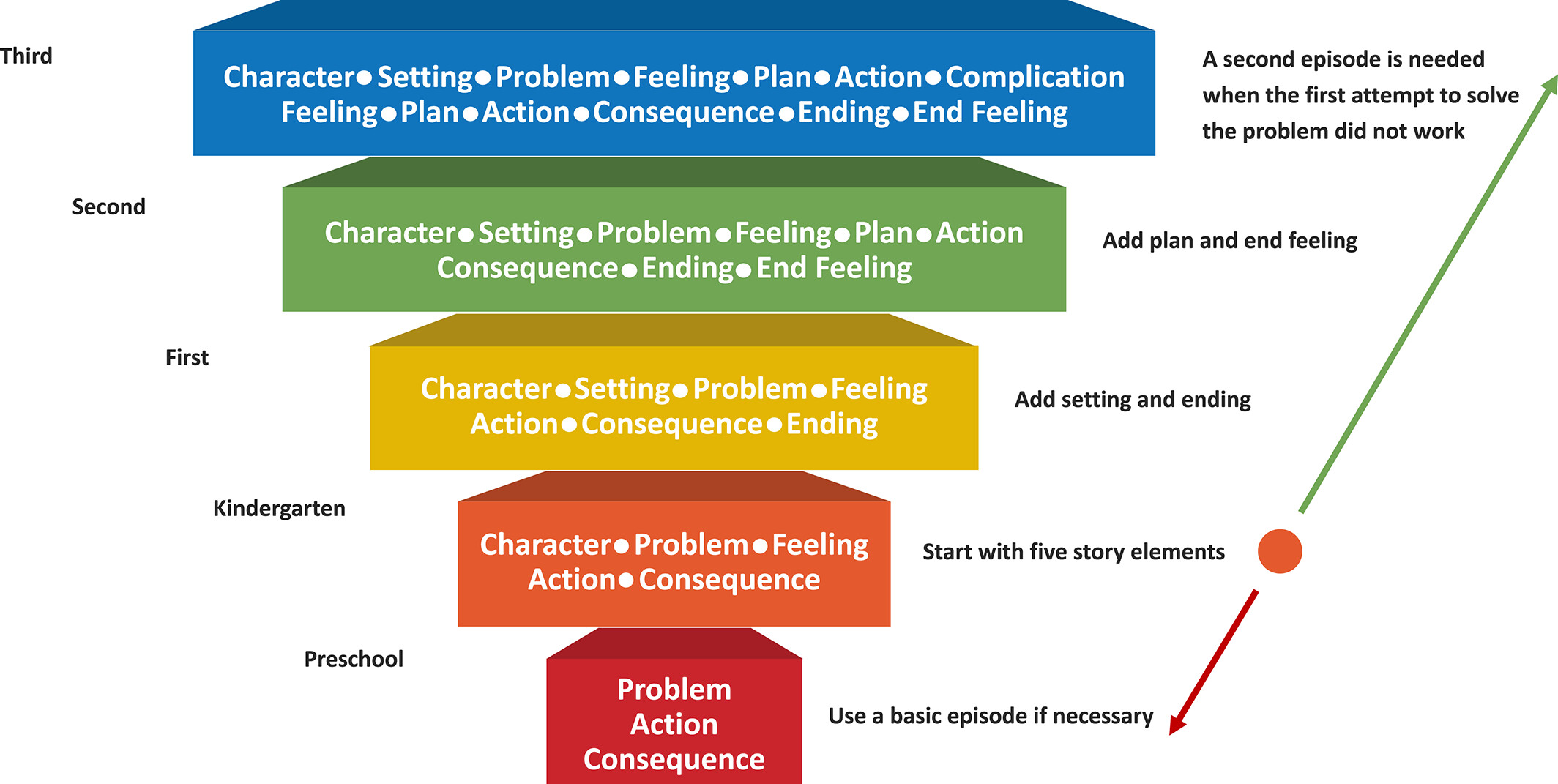

Figure 2

For young children (e.g., three to five years old), students with significant disabilities, and those with limited English proficiency, we recommend starting with short (about 50–70 words) stories that contain all the main story grammar elements (i.e., character, problem, feeling, action, consequence). Only if necessary should model stories be reduced to the most basic story components of problem, attempted action to solve the problem and the consequence of that action (see Figure 2). Story grammar elements should never be taught in isolation because it removes the purpose for the simple stories for too long. They are necessary to begin with, but the complexity of model stories should increase gradually over time (Spencer & Petersen, 2020). If teachers do not modify the difficulty of stories students are asked to retell, learning stagnates. To avoid this, teachers should monitor individual students’ retelling skills and adjust the stories and intervention accordingly. Free narrative retell assessments are available at www. languagedynamicsgroup.com as part of the CUBED suite of literacy assessments. Each grade level (preschool to third) set of the Narrative Language Measures Listening includes 22–25 stories with easy-to-use scoring rubrics. Teachers can use whatever grade level is developmentally appropriate for individual students to monitor their progress or to inform differentiated instruction. story and voids the activity of meaning, and purpose and meaning promote motivation and generalisation (Gillam & Ukrainetz, 2006).

Once students can independently retell a simple story with the five main parts, add the setting and ending. As students become proficient, longer stories with more story grammar elements can be used (e.g., complication, plan, resolution, end feeling). Eventually, storybooks or students’ classroom curriculum can be used to help extend their newly acquired narrative knowledge and oral academic language skills to less contrived contexts. Starting with simple stories help students experience success and acquire the academic language skills needed to be successful with more challenging narratives.

One pitfall that should be avoided is continuing intervention with simple stories for too long. They are necessary to begin with, but the complexity of model stories should increase gradually over time (Spencer & Petersen, 2020). If teachers do not modify the difficulty of stories students are asked to retell, learning stagnates. To avoid this, teachers should monitor individual students’ retelling skills and adjust the stories and intervention accordingly. Free narrative retell assessments are available at www. languagedynamicsgroup.com as part of the CUBED suite of literacy assessments. Each grade level (preschool to third) set of the Narrative Language Measures Listening includes 22–25 stories with easy-to-use scoring rubrics. Teachers can use whatever grade level is developmentally appropriate for individual students to monitor their progress or to inform differentiated instruction.

Explicitly teach story grammar

When students understand the narrative discourse structures, it becomes easier to teach and practise other forms of complex language. The story grammar framework should be explicitly taught to students so that they can retell stories that include all the episodic features and as many additional story grammar elements as possible. Narrative structure does not take very long to establish so once students know the main parts of the story appropriate for their grade level (see Figure 2 for structures aligned with grade-level expectations), teachers can begin prompting students to use longer and more complex sentences and less common words. These sophisticated sentence structures are considered literate language because they are more common in written narratives (Benson, 2009).

Therefore, teaching and practising them through an easier modality (i.e., oral) will decrease the demands of understanding complex sentences when they appear in written material.

It is important that storytelling remains fun for students and that they are successful, so the demands should be increased gradually. These are also areas in which differentiation can occur.

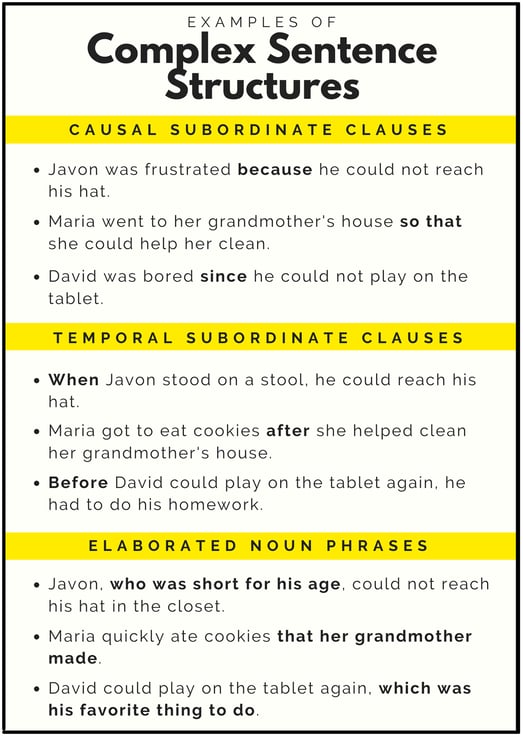

For example, all students in the large or small group can be expected to retell a story with the five main parts, but some students can be prompted to use complex sentences or precise vocabulary (e.g., splashed, filthy). As soon as students are ready and capable, they should be prompted to use causal and temporal subordination and elaborated noun phrases. See Figure 3 for examples of these complex sentences.

Figure 3. Examples of complex sentence structures

Use visuals when possible

Icons, gestures, illustrations, photos, props and videos can all be used to support students’ storytelling. Ideally, there is one image for every story grammar element included in a model story, at least in the beginning. If the five main story elements are taught, including character, problem, feeling, action and ending, then five images will help students to use at least one sentence per picture.

When students generate their own stories, teachers can draw the students’ story parts on a whiteboard or sticky notes. This strategy is known as pictography and can be a fun way to capture students’ narrative creations (Gillam & Ukrainetz, 2006). Icons or symbols can facilitate learning the story grammar framework (Pico et al., 2021), making the abstract schema more concrete for students, especially those with disabilities (Spencer et al., 2013). In some storytelling interventions, students make gestures to correspond to the story parts (see video demonstrations at www. languagedynamicsgroup.com).

As students retell the model story, icons or gestures offer some support, but less than illustrations or pictures. Illustrations and pictures would correspond to a specific story, whereas icons and gestures can be used generically with any story. Likewise, icons or gestures can serve as prompts for students as they generate personal or fictional stories.

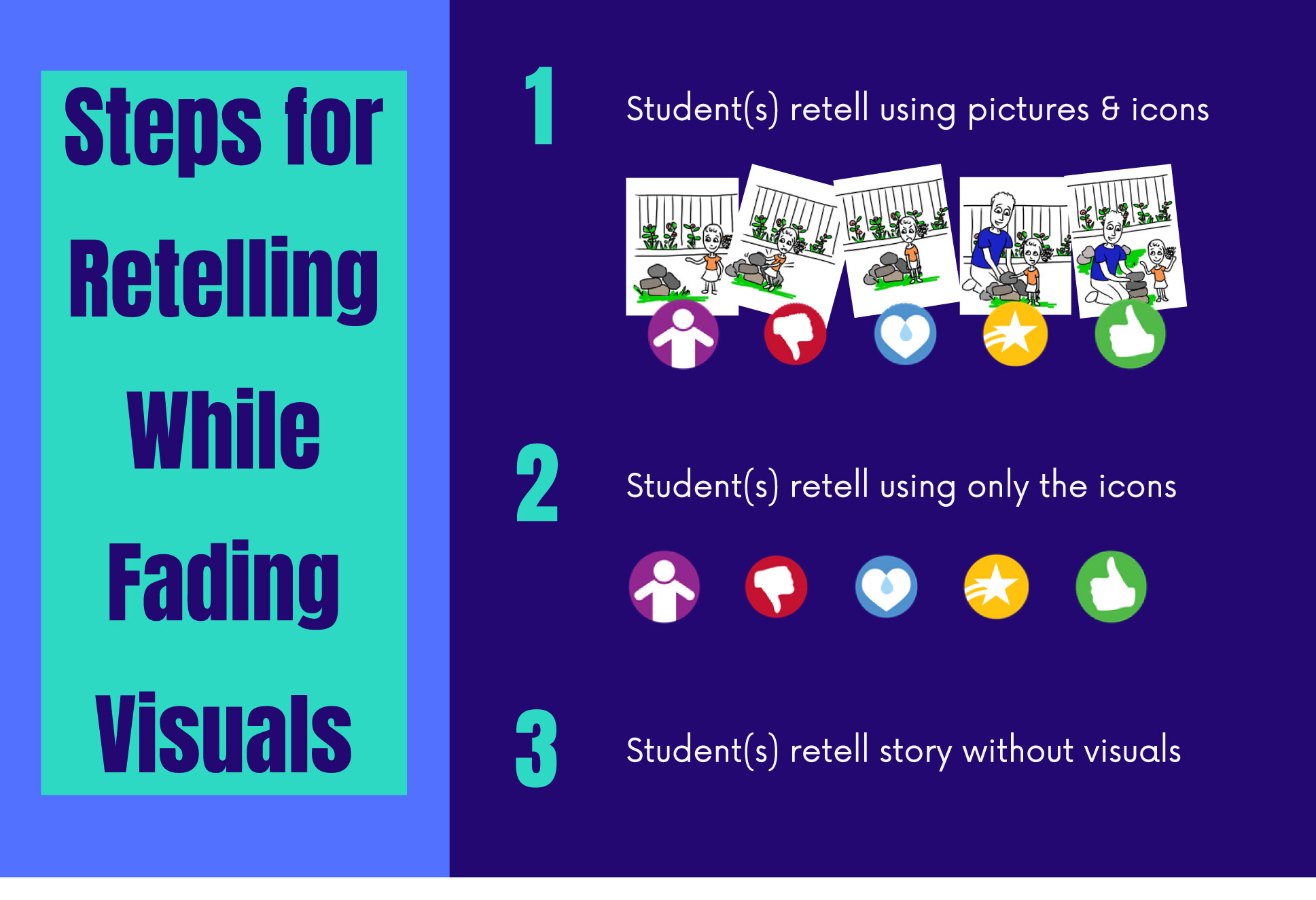

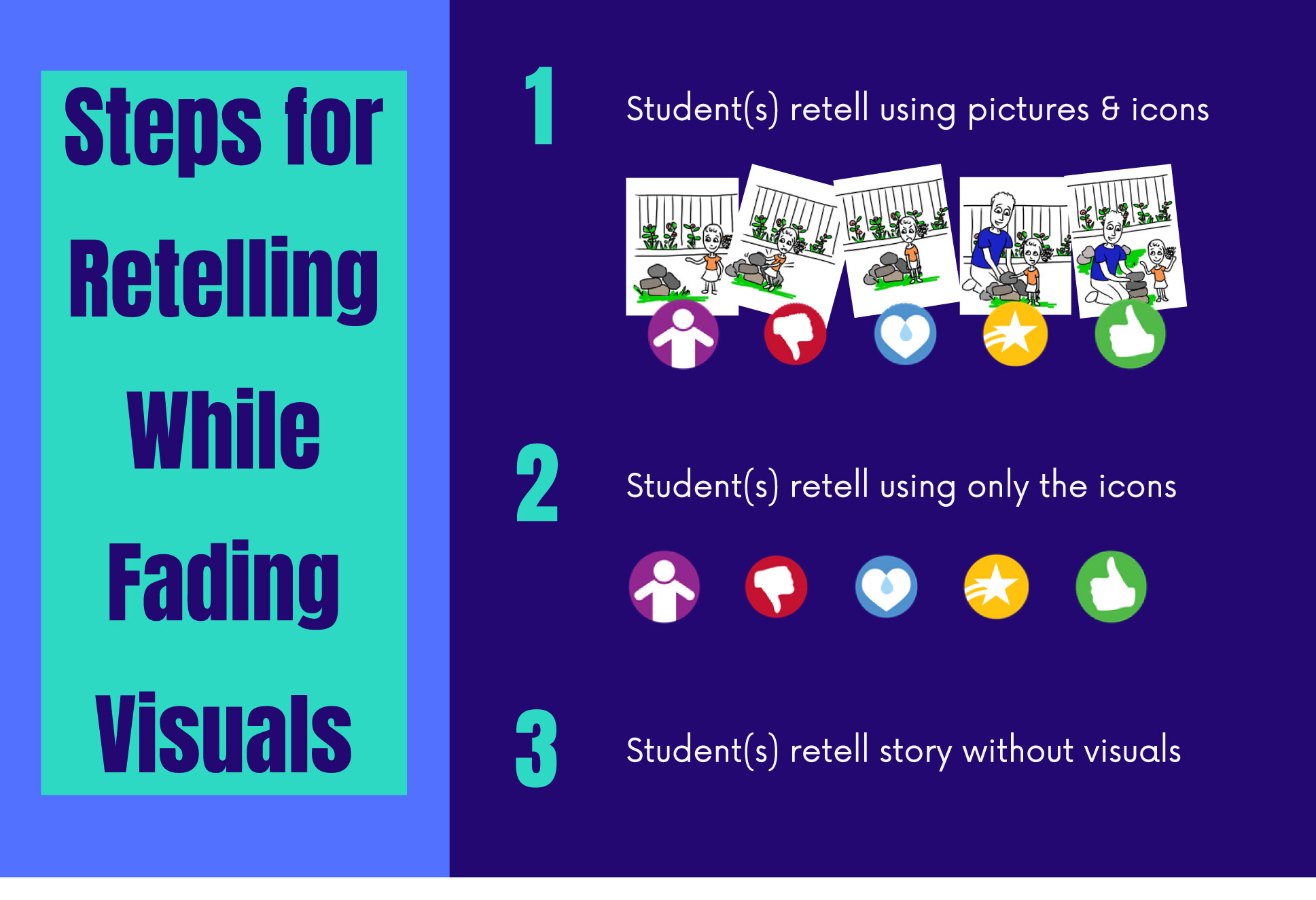

Visuals are powerful prompts for teaching narratives, but to avoid prompt dependency, they should be faded as quickly as possible. This is because in typical reading comprehension and writing tasks, students do not routinely have the benefit of visuals. Fading of any visual supports will prepare students for the higher demands of reading and writing. Ideally, students will be able to retell a story they heard (or read) independently and to generate personal and fictional stories in oral and written form. The fading of visuals within every intervention session helps to facilitate students’ independence with these tasks, as well as sharpen cognitive repertoires. Figure 4 shows an example of steps for retelling while fading visual supports.

These steps have been used in several storytelling intervention studies with great success and with a wide range of students (Spencer et al., 2013, 2020).

Figure 4. Example steps for fading visuals

Use effective and efficient prompts to individualise

Even when visuals are used, teachers will need to consistently model the language they want students to produce and prompt them to imitate the target skills. We recommend a simple, two-step prompting procedure to provide students with the right level of support, without frustrating them with lengthy least-to-most prompt hierarchies. For prompting students to include a story grammar element they may have forgotten (e.g., action), teachers can first ask a wh- question related to that part (e.g., “What did he do to fix his problem?”). If the student can retell the missing part with just the question, they can continue with the story. However, if the question prompt is ineffective, the second step is to model what the student should say and ask them to repeat the model (e.g., “He asked his mother for a bandage. Now you say that.”).

If a student uses a simple sentence when the teacher expects a longer more complex one, the recommended prompt is to model what the student should say and ask them to repeat it (e.g., “Say it like this. Listen. He was sad because he fell.”). The same type of model-imitate prompt can be used to get students to use specific vocabulary words (e.g., “He splashed into the puddle. You say it like that.”). The models and what teachers expect of students should be shortened or lengthened according to students’ individual abilities.

Promote generative language, not memorisation

It is imperative that teachers promote generative language rather than memorisation during storytelling activities. There are several ways to avoid leading students into rote learning. First, model different stories in consecutive intervention sessions. The goal is for them to learn the underlying structures of stories and the language patterns used to tell stories generally. These are abstract concepts and students need multiple examples of stories with those patterns to understand them (Spencer & Petersen, 2020). That is not to say that stories can never be repeated. When it is time to increase the complexity of models, return to stories used previously, but make them longer or require the students to use longer sentences or less common vocabulary words. That way, there is something new to learn even when they know the gist of the story.

Second, vary the sentences that students are prompted to say. There are many sentence patterns students need to learn. The more patterns they learn the more likely students will recombine learned clauses to produce novel sentences. For example, students can say, “He fell in the mud”, or “He got all dirty because of the mud”, or “Mud was all over him.” All these sentences describe the problem of the story using different sentence patterns.

Third, reinforce and praise response variation and novel sentences students produce. Even if it is not the most complex sentence, if a student recombines words and patterns in a manner they have never heard before, this is generative language and warrants celebration.

Extend storytelling into classroom routines and beyond the classroom

Once students learn the storytelling basics, students’ narratives can take on many forms and functions, and storytelling activities can occur anywhere and anytime. For instance, narratives may include storylines about relevant social situations such as bullying, peer pressure and tattling. Teachers can craft their own stories to be relatable to their students and teach problem solving. Just as students can learn the social–emotional content embedded in narratives, cultural expectations and traditions can be transmitted through storytelling. Teachers can give students opportunities to tell stories that originate from their family’s culture, as many students are exposed to oral storytelling traditions at home (Au, 1993). Consider drawing ideas for stories to use in the classroom from cultural activities students engage in at home.

Storytelling activities do not need to be limited to teacher–student interactions either. Students can be divided into pairs to take turns retelling a story (e.g., turn-n-tell). During snack or lunch time, students can tell each other stories.

Partner retelling can be incorporated into transition times such as when students must wait or move from one activity to another. This type of ‘transition listen’ is a way to embed storytelling into less structured parts of the daily routine while still making the time productive.

Students can be encouraged to tell family members stories they learn in class. If sticky notes were used during intervention, students can take their pictography home. They should be allowed to tell the stories to family members in whatever language is most comfortable for them. Because storytelling relies on cognitive schemas, once established they are present in all the languages students use.

Finally, oral storytelling can be done remotely (e.g., Zoom, Teams). Teachers can use short YouTube videos, images in PowerPoint slides, or Boom! decks to prompt a virtual storytelling exchange. Teachers can start by creating (or reading a prepared story) and then have students take turns retelling it or generating a story for the whole group, as partners in breakout rooms or to a family member. The possibilities are endless. The only critical feature is that students should have many opportunities to tell and retell stories.

Wrap up

There is a clear, urgent need to address oral academic language in schools due to its integral relation to reading and writing. A focus on narratives offers a promising approach for accomplishing this. We presented oral storytelling as a versatile option for promoting academic language of diverse students and offered recommendations for getting started. Although the recommendations are supported by a solid experimental literature (Favot et al., 2020; Pico et al., 2021; Stetter & Hughes, 2010) showing the effects of monolingual and bilingual oral storytelling interventions on listening comprehension, vocabulary, personal generations, reading comprehension and writing of students in preschool to third grade, with and without disabilities (Gillam & Gillam, 2016; Hessling & Schuele, 2020; Petersen et al., 2020, 2022; Spencer et al., 2013, 2020), the true test will be in its transportability to real-world classrooms. Teachers are invited to explore how oral storytelling activities can enhance their literacy instruction and examine the extent to which narratives bridge oral and written language.

The additive social–emotional benefits of oral storytelling should not be underestimated. Although the research base is less developed for social domains, a focus on narratives may simultaneously promote social skills and language development. We know that children who can tell stories proficiently are able to express emotions and report abuse (Fong et al., 2020). As a sense-making device, storytelling can help children understand the world and heal from trauma (McCabe, 2017). At this time when students’ oral language and social– emotional development is at serious risk, an approach that can enhance students’ social well-being, in addition to their academic achievement, is sorely needed.

Take action!

Guidelines for putting oral storytelling into action in your classroom:

-

Teach using retelling, then generalise to personal and fictional

-

Model simple stories and increase their complexity over time.

-

Teach story grammar before complex sentences and vocabulary.

-

Use visuals, when possible, but fade

-

Use effective and efficient prompts to individualise.

-

Promote generative language not memorisation.

- Extend storytelling into classroom routines and beyond the classroom.

Conflict of interest

Dr Spencer is an author of a commercialised narrative program and receives financial benefits related to its sale. Copyrighted images have been reproduced with permission. The authors did not receive funding from public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors to write this article.

More to explore

This article originally appeared in Volume 76, Issue 5 (pp. 525-534) of

The Reading Teacher.

Dr Trina Spencer is the director of Juniper Gardens Children’s Project and a professor in the Applied Behavioral Sciences department at University of Kansas. She holds a courtesy appointment in the department of Speech-Language-Hearing Sciences, as well. Dr Spencer values researcher–practitioner partnerships, community engagement, and cross disciplinary collaborations to accomplish high impact and innovative applied research. She teaches doctoral seminars on intervention design and implementation research, as well as undergraduate research in the community for the promotion of equitable education and opportunities for diverse learners.

Dr Chelsea Pierce is Behavior Specialist at a Title 1 Elementary School in Orange County, Florida. After serving students as a Special Education teacher, she worked with the Center for Autism and Related Disabilities (CARD) at the University of Central Florida, as well as CARD at the University of Florida (UF) Health Jacksonville. She worked for the UF Health Neurodevelopmental Pediatric Center, serving on the Multidisciplinary Developmental Assessment Team and administering assessments and consultations through the Florida Diagnostic Learning and Resource Systems, Multidisciplinary Center (FDLRS-MDC). Dr Pierce has presented at local and state-wide conferences in areas of interest, including the use of visual supports and behavior management strategies. She is passionate about supporting families and teachers of children with complex needs.

This article appeared in the September 2023 edition of Nomanis.