But what if there was a screening test for COVID-19?

While COVID-19 plays havoc with our minds, our healthcare workers and our economy, let’s just imagine that a COVID-19 Screening Check was available from tomorrow. We’ll call it CSC for short. In the spirit of any screening check (think breast screening, hearing screening, antenatal ultrasound screening), the CSC acts as a population-based preventative measure for early detection of the virus. While your imagination is running wild about the CSC, let’s also assume that those identified as positive on the CSC, will be eligible for early, evidence-based medical care. Let’s also assume that for most people (say about 80 per cent), the treatment is short, sharp and effective; well before the virus causes fever, fatigue and fear. What a huge relief and wonderful safety net that would be. What a cause for celebration.

By Tanya Serry

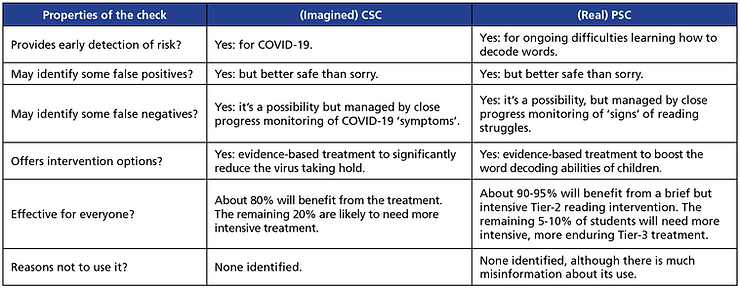

But what if we substituted CSC for PSC: the Phonics Screening Check? Would there be as much fanfare? Unfortunately, the answer is no, even though the PSC performs a similar function as our imagined CSC, but in relation to identifying students who are not tracking as expected in learning how to decode. It’s just that reading difficulties are a slow-burn virus that can take a lot longer to declare themselves, unlike COVID-19, which has a short incubation period. More about that later.

Background to the Phonics Screening Check

The Phonics Screening Check commenced in the UK in 2012. According to the South Australian Department for Education, which had the foresight in 2018 to trial the check statewide across publicly funded schools, the check is “… a short, simple assessment that helps teachers to measure how well students are learning to decode and blend letters into sounds – one of the building blocks for reading”.

The Check (note the word ‘check’ and not ‘test’) is conducted towards the latter half of Year 1 to monitor students’ progress in learning to decode words and in particular, to achieve the early identification of children struggling with decoding. The PSC takes between four and seven minutes to administer and consists of 40 items: 20 real words and 20 pseudowords. Herein lies the rub – ‘pseudowords’; loved by some, despised by others, misunderstood by many.

Real words could be for example: ITS, SUM or THIRD while pseudowords could be OSK, PAB or DARP. You’ll see that the pseudowords are all phonologically legal and phonotactically identical (respectively). I can’t show you a picture of test items as they are not labelled for re-use. However, the reality is that every word that children encounter, real or pseudo, is new for a novice reader at least once. All the PSC is doing is determining whether Year 1 students can decode phonologically legal combinations. Perhaps in an ideal world, where there was overarching support for the concept of a PSC, the entire check could be pseudowords. That would really be the purest way of tracking students’ decoding abilities; but for now, a bridge too far. It would mean, however, that we would not see ill-informed comments reported in newspapers such as, “Apparently, puzzling over the sounds of ‘flisp’ is going to help children learn to read and write”.

So how does the Phonics Screening Check stack up against the CSC?

If we reflect on the likely support for the imagined CSC and the real-life PSC, it would go something like this:

The good news

On August 2nd, a media release was circulated by the Hon. Dan Tehan MP (Federal Minister for Education)1 headed ‘2020, Free phonics check for all Year 1 students’. In this release, the Minister was quoted as saying, “Importantly, Phonics Check results provide teachers with a useful picture of where individual students are at in their reading, so they can implement the right support for those who are struggling…”

How good is that?

Well yes, it’s good if you support the Phonics Check (like I do). And if you do support the Phonics Check, implicitly that means that you understand:

-

That the ultimate aim of reading is to gain meaning;

-

That Gough and Tunmer’s (1986) Simple View of Reading (which states that reading is a product of being able to decode words and understand spoken language), is theoretically sound;

-

That novice readers (5- to 6-year-old students) need to be taught how to ‘crack the code’ of English;

-

That learning to decode accurately and efficiently is the first, crucial step to becoming a competent reader;

-

That not all children will learn to ‘crack the code’ without explicit teaching, but these children do not necessarily have a learning difficulty;

-

That structured literacy using a synthetic phonics approach is the safest way to ensure that children learn to decode words;

-

That a systematic scope and sequence is superior (safer and more trustworthy) to a non-systematic approach (see here and here), and;

-

That humans were not born “wired to read” (and spell) and therefore need to be taught, ideally in a systematic and explicit way.

Why the backlash?

Those who challenge the value of the PSC use the straw-man argument that says “decoding alone does not a good reader make”. But that’s just not correct as shown by the evidence (see for example here and here). Take the Simple View of Reading which states, in the most elegant way, that being a competent reader comes about by being able to (i) decode well and (ii) have a solid grasp of oral language comprehension. Then there is the very important work of Professor David Kilpatrick who has demystified for us all, that critical step of moving from decoding in a rather mechanistic; sound-it-out way to developing orthographic mapping skills for fluent effortless word reading (the 70 minute investment in the hyperlinked YouTube video above is well worth it).

The sound-it-out decoding part, which is all the PSC is used for, opens the door to becoming a competent reader. That’s all. In the same way that we would be fist-punching for that imagined CSC, universal acceptance of the PSC, which is at our fingertips and on our iPads, should elicit the same joy. The joy of reading, in fact.

1. Since the time of writing, the Hon. Dan Tehan has been replaced as Federal Education Minister by the Hon. Alan Tudge.

This article originally appeared on The Snow Report.

Tanya Serry (@tserry2504 on Twitter) joined the School of Education at La Trobe University in 2020 as A/Prof (Literacy & Reading). Together with Prof Pamela Snow, she is the co-director of the SOLAR Lab. Prior to joining the School of Education, Tanya was a senior lecturer and discipline lead teaching Speech Pathology, also at La Trobe University. Tanya’s research and teaching are focused on language and literacy and learning difficulties among students from the early years through to tertiary students as well as students experiencing social disadvantage. Tanya’s research and teaching centres on how to facilitate greater collaboration between educators, parents, speech pathologists and psychologists.

Associate Professor Tanya Serry is an Advisory Panel Member for the Australian Government Department of Education, Skills and Employment in relation to the development of the 2020 online Phonics Screening Check. All views expressed in this blog are opinions of the author alone.

This article appeared in the June 2021 edition of Nomanis.