Review – ‘A walk through the landscape of writing: Insights from a program of writing research’

Review – ‘A walk through the landscape of writing: Insights from a program of writing research’

In 2017, Judith Hochman and Natalie Wexler published The Writing Revolution (TWR): a book outlining a new way of thinking about and teaching writing. A key feature that sets TWR apart from other approaches is its suggestion that school students should only focus on sentence-level writing until this is mastered (i.e., the purposes and structures of written genres should only be added after a lot of work on sentences).

By Damon Thomas

This is a somewhat controversial idea if you believe that the sentences we write are always influenced by what and why we’re writing. It also introduces the risk that children will spend much of their primary schooling (and even their secondary schooling, depending on when they start) repeating the same set of basic sentence tasks in every subject. But in taking a developmental approach, Hochman and Wexler argue that learning to write is challenging for young learners and focusing solely on sentences in the beginning greatly reduces their cognitive load. Hochman and Wexler say you can’t expect a child to write a strong text, let alone a strong paragraph, until they can write strong sentences. A brief document has been published on the TWR website outlining the theoretical ideas that underpin the approach, which you can read about here.

As I mentioned in my last post on TWR, there haven’t been any research studies or reports to verify if teaching the TWR way enables or constrains writing development … until now.

A reader named ‘Rebecca A’ left a comment on my last post about TWR to say she’d found a report by an independent research and evaluation firm (Metis Associates) into the efficacy of a TWR trial in New York. The firm partnered with TWR in 2017 and spent some years evaluating how it worked with 16 NYC partner schools and their teachers. Partner schools were given curriculum resources, professional development sessions in TWR, and onsite and offsite coaching by TWR staff.

Evaluating TWR

Metis Associates were interested in TWR writing assessment outcomes, outcomes from external standardised writing assessments and student attendance data. They compared the writing outcomes of students at partner schools with the outcomes of children at other schools. Teacher attitudes were also captured in end-of-year surveys.

This report did not go through a rigorous, peer-reviewed process, but if you are interested to know if TWR works, it’s probably the best evidence that’s currently out there. Also, keep in mind that the partner schools were very well supported by the TWR team with resourcing, PD and ongoing coaching. In that sense, you might consider this a report of TWR under ideal circumstances.

If you work at a school using TWR or if you’re interested in the approach, I’d recommend reading the full report here. I will summarise the key findings of the report in the rest of this article.

Key finding 1: Teacher attitudes

Teachers at partner schools reportedly found the TWR training useful for their teaching and got the most value from the online TWR resource library. School leaders liked being able to reach out to the TWR team for support if necessary. Some teachers wanted more independence from the strict sequence and focus of TWR activities. Most, though, found the approach had helped them to teach writing more effectively.

Key finding 2: Impact of TWR on student writing outcomes

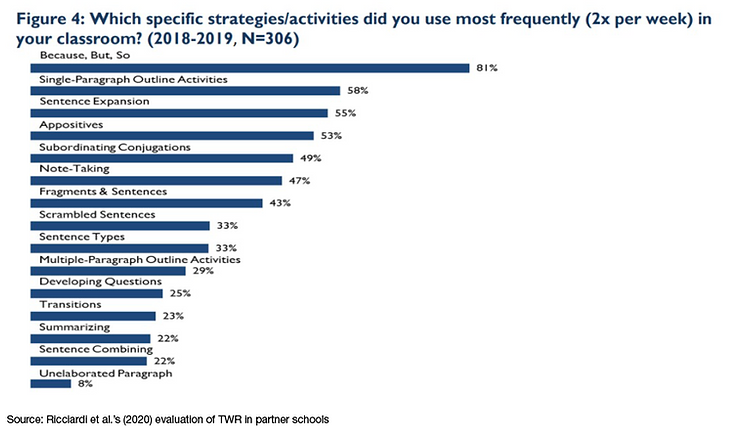

But what about the development of students’ writing skills? TWR seems to have made a positive difference at the partner schools. TWR instruction helped students in each grade to advance somewhat beyond the usual levels of achievement. It’s not possible to say much more about this since the presentation of results in the report is quite selective and we only see how the partner schools compared with non-partner schools for certain statistics, like graduation rates and grade promotion rates, which are likely to be influenced by all sorts of factors. The one writing assessment statistic that does include comparison schools is for the 2019 Regents assessment for students in Years 10, 11, and 12. In this case, students at TWR schools did better in Year 10. Results between TWR and comparison schools were similar in Year 11, while comparison schools did better in Year 12. So, a mixed result. Being behind other schools is not really an issue if everyone is doing well, but it’s not immediately clear from this report how these results compare with grade-level expectations or previous results at the same schools (see Figure 4 below).

Something that might explain the mixed outcome for senior secondary students is the tendency for teachers at partner schools to favour the basic sentence level strategies over paragraph or whole text/genre strategies in their teaching. Partner schools taught TWR in Year 3 through to Year 12, and 81% of teachers reported teaching the ‘because, but, so’ strategy regularly (i.e., more than two times per week). By comparison, evidence-based strategies like sentence combining were far less commonly taught (i.e., regularly taught by 22% of teachers). This suggests that it’s important for schools using TWR to be systematic and intentional about the strategies taught and to ensure that educators aren’t spending longer than needed on basic sentence-level activities. This would mean educators can get the most important of what TWR offers, which I would argue comes with the single and multiple paragraph outlines and genre work.

When only looking at partner school outcomes, the picture looks positive. The report shows percentages of students performing at Beginning, Developing, Proficient, Skilled, and Exceptional levels at the beginning and end of the year. At each partner school, percentages are all heading in the right direction with many more proficient and skilled writers at the end of the evaluation.

Conclusion

To summarise, in offering select outcomes and comparisons only, and in using metrics that aren’t entirely clear, the report highlights the need for rigorous, peer-reviewed studies to better understand how TWR works for different learners and teachers in different contexts. Despite its limitations, the report points to positive outcomes for the new approach to teaching writing. This is good news for the schools out there that have jumped on board the TWR train.

It also suggests that careful attention should be paid to the specific TWR strategies that dominate classroom instruction if students are to get the most out of it. If you are using the TWR approach, my advice would be not to spend a disproportionate amount of time on basic sentence work from the middle primary years, since well-supported approaches like Self-Regulated Strategy Development (SRSD) and genre pedagogy have shown students can (and should?) be writing simple texts that serve different purposes from a young age.

I remain greatly intrigued by TWR. It turns the writing instruction game on its head and has made me question whether other approaches expect too much from beginning writers. Its approach seems to line up nicely with cognitive load theory, in gradually building the complexity and expectation as learners are prepared for it. There’s a lot at stake though if this specific combination of strategies doesn’t actually prepare students for the considerable challenge of genre writing in the upper primary and secondary school years. You could follow its strategies diligently across the school years but inadvertently limit your students’ writing development (in time, more research will tell us if this is the case).

I realise it’s anecdotal, but my seven-year-old son (just finished Year 1) and I have been talking about argumentative/persuasive writing at home for the last few weeks and the discussions we’ve had and the writing he’s done as a result have been incredibly satisfying for both of us. To think that he should be limited to basic sentence writing and not think about and address different purposes of writing (like persuading others about matters of personal significance) for years into his primary schooling wouldn’t sit well with me after seeing what he’s capable of with basic support grounded in a firm knowledge of language and text structures and encouragement.

It’s also possible to see how students who struggle badly with writing could benefit from practice with basic sentence writing before much else. It was in a context filled with struggling writers that TWR was first conceived, and there it may be most useful.

References

Hochman, J. C., & Wexler, N. (2017). The writing revolution: A guide to advancing thinking through writing in all subjects and grades. Jossey-Bass.

Ricciardi, L., Zacharia, J., & Harnett, S. (2020). Evaluation of The Writing Revolution: Year 2 Report. Metis Associates. https://www.guidestar.org/ViewEdoc.waspx?eDocId=1956692

Damon Thomas [@DamonPThomas on Twitter] is a senior lecturer in literacy education at the University of Queensland. His current research interests include writing development, pedagogy, and assessment; systemic functional linguistics; argumentation; and dialogic pedagogies. Before starting his academic career, Damon was a primary school teacher in Tasmania.

This article appeared in the Dec 2022 edition of Nomanis.

Review – ‘A walk through the landscape of writing: Insights from a program of writing research’

What if there is no reading research on an issue?

Enhancing literacy learning outcomes for beginning readers: research results and teaching strategies