The SpellEx approach to teaching spelling

Learn about the importance of teaching spelling and how the SpellEx program can help students develop their spelling skills. Discover the components...

Good spelling is an extremely important skill for a literate person to possess. Accurate spelling assists readers to understand text they are reading and inaccurate spelling can make a text difficult to comprehend and be judged harshly by readers. The ability to spell well also helps with writing, as it allows the writer to devote more of their mental resources to composition rather than being distracted by how to spell words. Spelling is also important for reading, and vice versa. Reading skills such as phonemic awareness and phonics are necessary for good spelling to develop, and instruction in spelling can result in better reading (Graham & Hebert, 2011 ; Graham & Santangelo, 2014 ; Moats, 2005 ).

By Alison Madelaine

Over the last several decades spelling has been considered a low curriculum priority (Pan et al., 2021; Sayeski, 2011). The more mechanical aspects of writing such as spelling and handwriting have been largely abandoned in favour of higher order writing skills ( Joshi et al., 2008). This has resulted in generations of students leaving school with below satisfactory spelling skills, leading many to consider how spelling should be taught.

Use of word lists

Traditionally, a common approach to the teaching of spelling has involved the rote learning of lists of words, with an emphasis on the visual information each word conveys. In fact, using lists of words to ‘teach’ spelling has persisted since early in the 20th century (Pan et al., 2021). If using this approach, a teacher might prepare a list of words for their students to learn for the week. This is given to the students on Monday, and they are tested on Friday. Spelling word lists may come from other areas of the curriculum, from children’s own writing or from a spelling program. During the week, some light teaching may occur to practise these words, for example, copying the words out multiple times or writing the words in a sentence, but essentially there is often little, if any, in-depth instruction around the nature of the English language to assist children in their understanding of how the system works. The main problem with this type of approach is the absence of any real instruction in spelling.

Are lists always a problem?

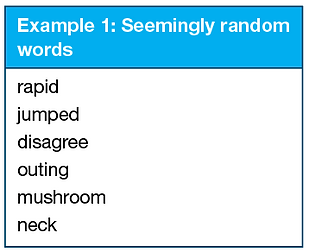

It is important to note here that it may be a little unfair to completely dismiss the use of word lists as part of spelling instruction. The examples below show three lists of words. In Example 1, the words are seemingly random. The list includes words with many different types of phonological, orthographic and morphological features; for example, there are words with one, two, and three syllables, different digraphs (ee, ou, sh, oo, ck) and different affixes (ed, dis, ing). Lists of words that are completely orthographically unrelated promote rote learning as the main spelling strategy and force children to focus on the visual features of a word. It is likely that the ‘instruction’ that would accompany this list would involve writing the words many times using the Look, Say, Cover, Write, Check method, for example.

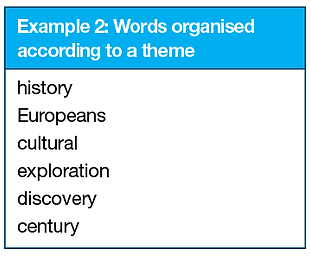

In Example 2, the words are organised according to a theme. Again, the words are orthographically unrelated and the list contains different examples of morphographs (Europeans, cultural, discovery). A morphograph is the spelling or orthographic representation of the smallest unit of meaning within a word. This list might be used during a history unit and students would probably practise spelling these words in the context of writing about history.

In Example 3, the words are organised according to a common suffix (ion). The spelling instruction that accompanies this list of words would include instruction in morphology where appropriate (for example, changing the bases ‘act’ to ‘action’, ‘donate’ to ‘donation’ and ‘operate’ to ‘operation’).

Using lists of orthographically unrelated words to teach spelling, as in Examples 1 and 2, is more problematic than using lists of words that are related in some way, as in Example 3, because the amount of new content presented in Examples 1 and 2 is larger and requires more memorisation. In Example 3, an understanding of the structure of words is being built whereas in Examples 1 and 2, it would be difficult for children to notice a pattern. As can be seen in the examples above, the words presented to children has implications for spelling instruction.

How should spelling be taught?

English is considered by many to be highly irregular but research indicates that about 50% of all words can be spelled accurately based on regular letter-sound relationships. A further 34% are regular except for one sound and about 12% can be spelled using knowledge of word origin and word meaning. This leaves just 4% of English words that are truly irregular (Joshi et al., 2008). This may surprise those who see only exceptions to every rule or pattern, but it has important implications for the teaching of spelling. Evidence that English spelling is actually highly regular suggests that there is value in teaching spelling rules and conventions, and that spelling instruction should be language-based rather than based on rote learning of individual words.

Language-based spelling instruction occurs when children are explicitly taught linguistic concepts. This includes speech sounds, grapheme-phoneme correspondences (GPCs), word origins and morphology (meaningful parts of words) (Joshi et al., 2008). Children are taught to think about language and the internal structure of words rather than memorising the spellings of individual words. With this type of spelling instruction, children are able to spell many more words than it would be possible for them to memorise, and includes the words used as part of spelling instruction and the application of knowledge to novel words. There is far more empirical support for the provision of language-based spelling instruction than that based mainly on rote memorisation due to the generalising potential offered by language-based instruction (Berninger et al., 2000; Joshi et al., 2008; Moats, 2009; Moats, 2019).

In addition to being language-based, spelling should be taught via explicit instruction. Explicit instruction has been found to be instructionally effective in general (Burton, Nunes, & Evangelou, 2021; Graham & Santangelo, 2014; Hughes et al., 2017; Westwood, 2022). It is a teacher-directed approach with features such as well-sequenced lessons, clear and concise language, guided practice, frequent student responses, cumulative review, distributed practice, and systematic (and immediate) error correction.

Error correction is an important consideration with regard to the teaching of spelling as the timing of this is often too late. It is necessary to deliver corrective feedback as soon as possible after a child makes a response (in this case, spelling a word or words) in order to facilitate high rates of success and reduce the chance of children practising errors (Archer & Hughes, 2011). Children should be given immediate feedback during teaching ( Ashman, 2018 ) not days afterwards as is often the case with weekly spelling tests.

As well as providing explicit, language-based spelling instruction, the teaching of spelling should be integrated with reading and writing instruction, especially in the first few years of formal schooling when children are learning the alphabetic code. Many researchers have documented the close relationship between reading and writing ( Ehri, 2000; Graham, 2020; Moats, 2005)Instruction organised in this way is more efficient as the reciprocal skills of reading and writing (including handwriting and spelling) are taught together and reinforce each other.

Conclusion

Although more traditional approaches to spelling instruction have involved weekly lists of words to be learned and then tested, it is not necessary or desirable to organise spelling instruction and assessment in this way. In order to avoid relying on memorising words as the main spelling strategy, evidence-based and language-based explicit spelling instruction should be provided to children, along with regular assessment.

References

Archer, A. L., & Hughes, C. A. (2011). Explicit instruction: Effective and efficient teaching. The Guilford Press.

Ashman, G. (2018). The truth about teaching: An evidence-informed guide for new teachers. SAGE Publications.

Berninger, V. W., Vaughan, K., Abbott, R. D., Brooks, A., Begayis, K., Curtin, G., Byrd, K., & Graham, S. (2000). Language-based spelling instruction: Teaching children to make multiple connections between spoken and written words. Learning Disability Quarterly, 23(2), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511141

Burton, L., Nunes, T., & Evangelou, M. (2021). Do children use logic to spell logician? Implicit versus explicit teaching of morphological spelling rules. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(4), 1231–1248. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12414

Ehri, L. C. (2000). Learning to read and learning to spell. Topics in Language Disorders, 20(3), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/00011363-200020030-00005

Graham, S. (2020). The sciences of reading and writing must become more fully integrated. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(1), 35-44. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.332

Graham, S., & Hebert, M. (2011). Writing to read: A meta-analysis of the impact of writing and writing instruction on reading. Harvard Educational Review, 81(4), 710–744. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.81.4.t2k0m13756113566

Graham, S., & Santangelo, T. (2014). Does spelling instruction make children better spellers, readers, and writers? A meta-analytic review. Reading and Writing, 27(9), 1703–1743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-014-9517-0

Hughes, C. A., Morris, J. R., Therrien, W. J., & Benson, S. K. (2017). Explicit instruction: Historical and contemporary contexts. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 32(3), 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/ldrp.12142

Joshi, M., Treiman, R., Carreker, S., & Moats, L. C. (2008). How words cast their spell: Spelling is an integral part of learning the language, not a matter of memorization. American Educator, Winter, 6–43.

Moats, L. C. (2005). How spelling supports reading: And how it is more regular and predictable than you may think. American Educator, 123(3), 12–43. Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/123/3/e425

Moats, L. C. (2009). Teaching spelling to children with language and learning disabilities. In G. A. Troia (Ed.), Instruction and Assessment for Struggling Writers: Evidence-based Practices (pp. 269–289). The Guilford Press.

Moats, L. (2019). An Opportunity to Unveil the Logic of Language. Perspectives on Language and Literacy, Summer, 17–20.

Pan, S. C., Rickard, T. C., & Bjork, R. A. (2021). Does spelling still matter – and if so, how should it be taught? Perspectives from contemporary and historical research. Educational Psychology Review, 33, 1523–1552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09611-y

Sayeski, K. L. (2011). Effective spelling instruction for children with learning disabilities. Intervention in School and Clinic, 47(2), 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451211414191

Westwood, P. (2022). Learning to spell: Enduring theories, recent research and current issues. In K. Wheldall & N. Bell (Eds.), Recent psychological perspectives on reading and spelling instruction (pp. 187–207). MRU Press.

Dr Alison Madelaine is a Senior Research Fellow within the MultiLit Research Unit at MultiLit Pty Ltd. She is also Clinical Director of the MultiLit Literacy Centres and has had hands-on experience teaching students with reading difficulties in Australia and South Carolina, USA. She has provided consultation around the delivery of MultiLit’s literacy programs to disadvantaged students in several projects, including those in Cape York, inner-city Sydney, and Sydney’s western suburbs.

This article appeared in the Dec 2022 edition of Nomanis.

Learn about the importance of teaching spelling and how the SpellEx program can help students develop their spelling skills. Discover the components...

Two sides of a single coin – speech-to-print, print-to-speech – let’s not devalue the currency

Nomanis Issue 16 Jennifer Buckingham – What is at the heart of the Science of Reading for teachers?