Last year, a report by the Education Policy Institute (EPI) investigating the impact of England’s phonics screening check (PSC) was released. The report interrogated a number of data sources but failed to find “a discernible positive impact of the PSC on the reading levels of primary-aged children in England”.

This conclusion seems at odds with what I understand of the PSC. I argued in a previous blog that the PSC has “driven dramatic improvements in pupils’ phonics knowledge”. Published research has linked these improvements to a “steady rise in performance in KS1”. Other research has talked about the importance of the PSC in guiding interventions for struggling readers and in refining classroom practice. The PSC has apparently been so successful that countries other than England are now doing it. So, how should we understand these different perspectives?

In this article, I’m going to argue that the EPI report hasn’t considered the right data, hasn’t formed well-justified hypotheses and has made strong conclusions that are not supported by the data.

What was the original purpose of the PSC?

The original purpose of the PSC was:

• to confirm that pupils have learned phonic decoding to an appropriate standard

• to identify children who require extra support to reach the required standard.

It was also ‘hoped’ that the impact would be felt more widely in

(a) encouraging schools to implement a rigorous phonics program; and

(b) increasing the number of pupils reading competently at the end of KS1 and KS2 (section 1.1).

I recount these original aims and aspirations because that’s how we should be assessing whether the PSC has done its job. Yet, that’s not what the EPI report has done: they’ve considered a wide range of data, including whether some groups of pupils pass the PSC at higher rates than others, KS1 and KS2 reading and writing scores, PIRLS scores and teacher surveys. The report does not even address whether the PSC has fulfilled its original purpose.

So, has the PSC fulfilled its original purpose?

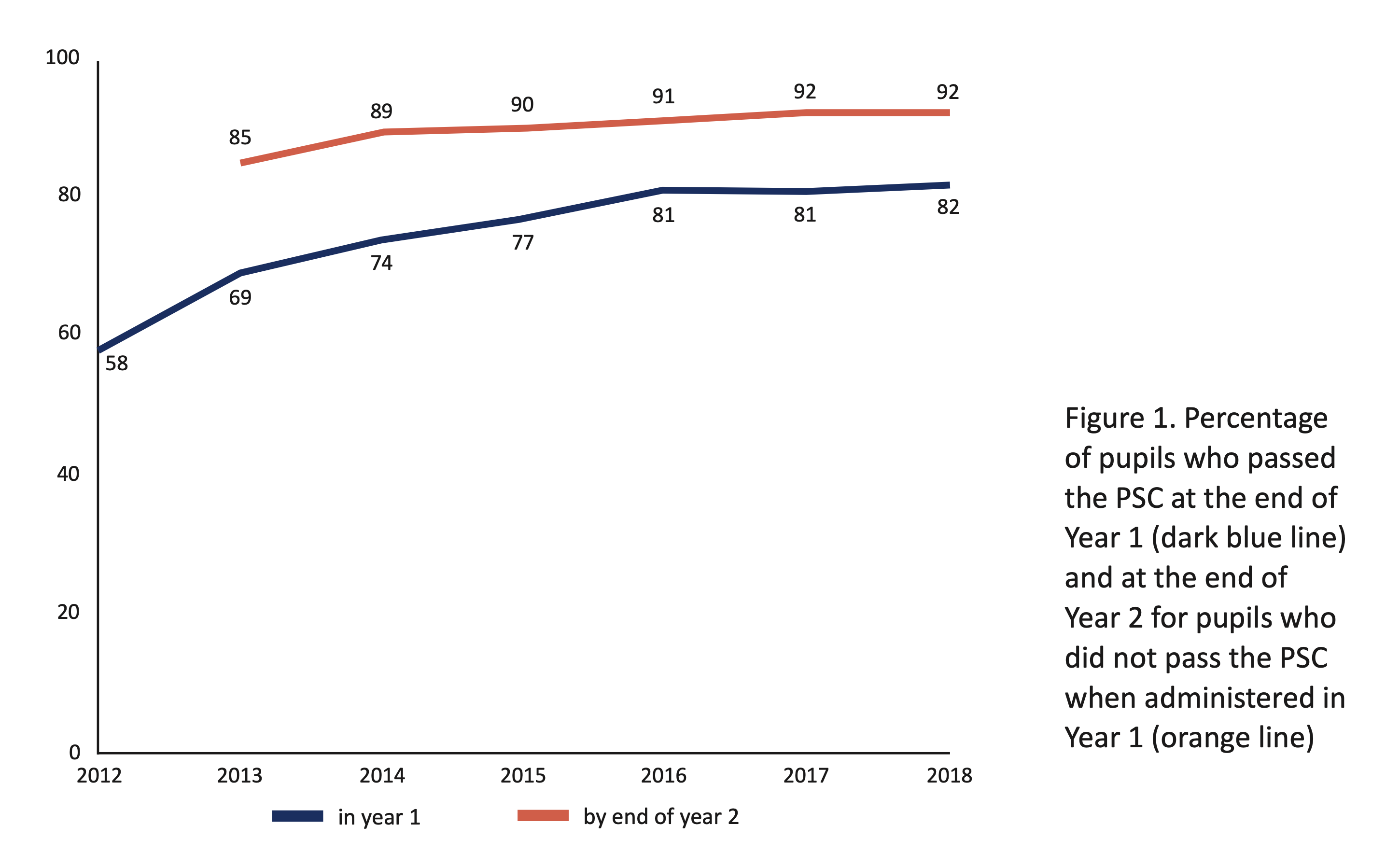

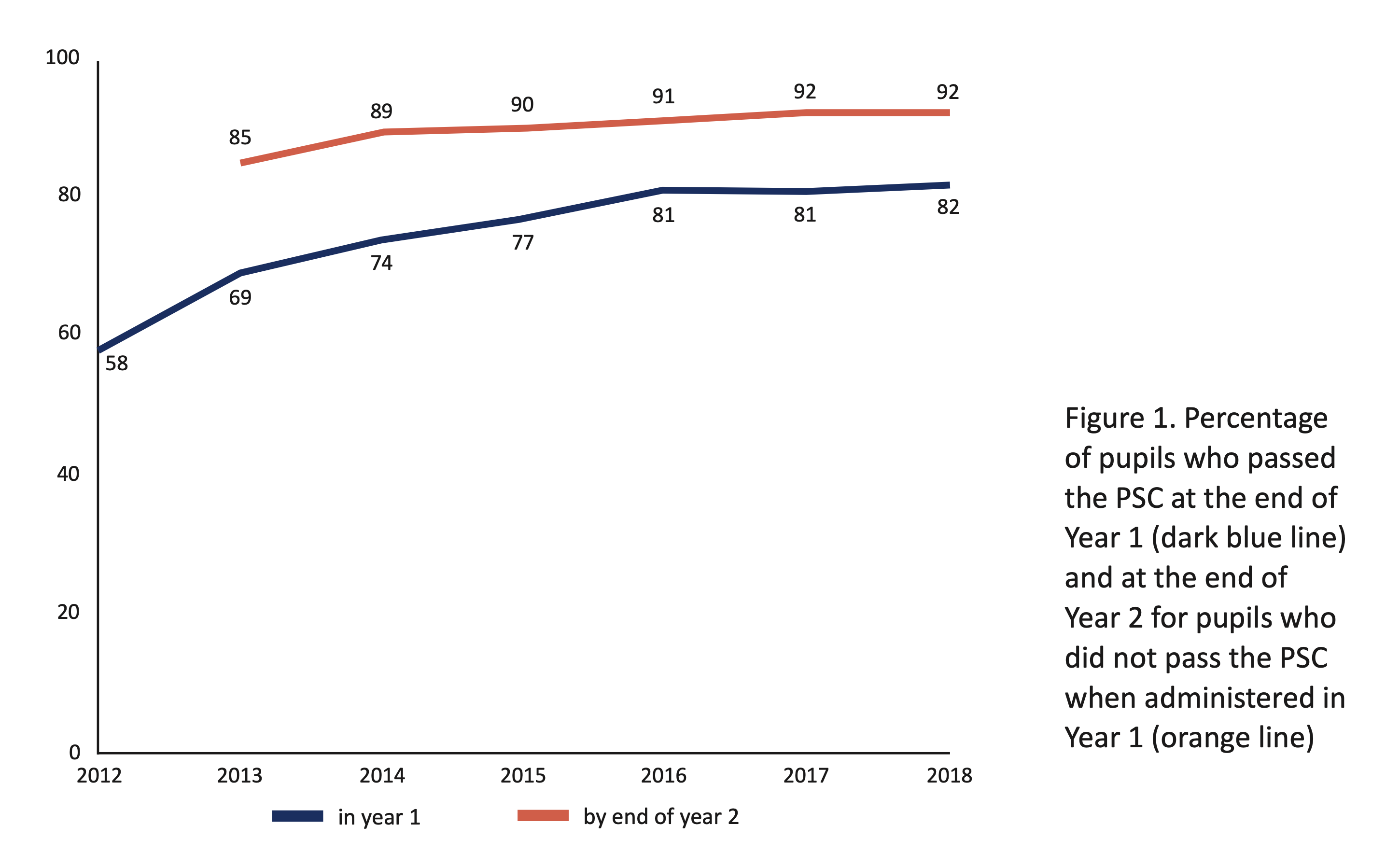

It is manifestly clear that the PSC has fulfilled its original purpose of assessing pupils’ decoding skills and identifying children in need of extra support. The dark blue line in Figure 1 shows the percentage of pupils meeting the PSC pass mark at the end of Year 1. Pupils who do not meet the pass mark receive additional support and retake the PSC at the end of Year 2; the orange line shows scores for those pupils. Overall, the PSC has provided schools with a straightforward means of assessing pupils’ decoding ability in a manner shown to be valid.